Ransomware attacks represent a significant cybersecurity threat, affecting various sectors and individuals. This study examines a comprehensive dataset of ransomware payments and chat logs to better understand the strategies and patterns of attackers. The analysis focuses on major ransomware groups, including LockBit, Hive, BlackMatter, and Conti, covering 200 incidents from 2020 to the end of 2023. The findings offer insight into the financial motivations and evolving trends within the ransomware landscape. The primary motivation behind ransomware attacks is financial gain. Cybercriminals demand ransoms in cryptocurrency, which is difficult to trace, in exchange for the decryption key to unlock the victim’s devices. According to the dataset under analysis (that must be considered limited and based on my visibility only) the total sum of initial ransoms demanded is 457,444,539 (!!) dollars. However, the total sum of negotiated ransoms is 273,655,572 (!) dollars, which represents a decrease of 40.18%. This suggests that victims often negotiate with the attackers to reduce the ransom amount. The descriptive statistics show that the average initial ransom demanded is $ 3,290,970 while the average negotiated ransom is $ 1,968,750. The record for the highest initial ransom demanded is $ 80,000,000 (LockBit 3.0) while the highest negotiated ransom is $ 25,000,000.

DATA INSIGHTS

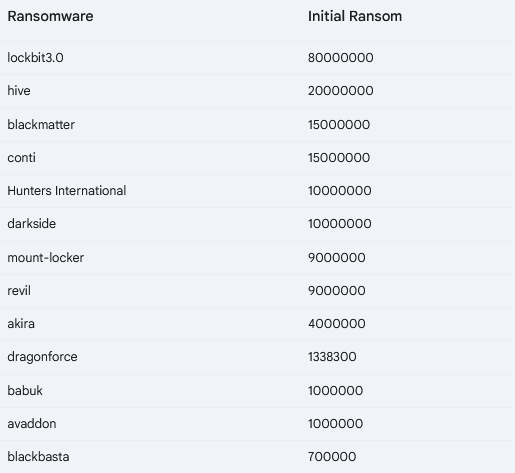

The table below shows the highest ransom demand for each ransomware in descending order. ‘Ransomware’ is the name of the ransomware used in the attack, and ‘Initial Ransom’ is the amount of ransom demanded.

The analysis of ransomware attacks reveals a broad range of ransom demands, from $20,000 to a staggering $80,000,000. Lockbit3.0 stands out with the highest ransom demand, reaching $80,000,000, significantly surpassing Hive, which demanded $20,000,000. Both Blackmatter and Conti demanded $15,000,000, further illustrating the substantial financial motivations behind such attacks. Interestingly, some ransomware collectives, like Blackbasta, Darkside, and Mallox, display varying ransom demands, indicating an adaptable approach to extortion. This variability underscores the dynamic nature of the ransomware landscape, where attackers adjust their strategies based on the perceived vulnerability and financial capacity of their targets.

On the lower end of the spectrum, Mallox‘s lowest ransom demand of $20,000 demonstrates that even smaller sums can incentivize malicious actors. This highlights the pervasive nature of the threat, where no target may be considered too small or insignificant for attackers seeking financial gain. Overall, the data paints a concerning picture of the growing threat of ransomware attacks, driven by substantial financial incentives and characterized by a wide range of ransom demands. The average difference between the initial and negotiated ransom, for each ransomware group, represents the average amount by which the negotiated ransom was lower than the initially demanded ransom. This statistic can provide insights into the negotiation dynamics between the attackers and the victims, as well as the potential for reducing the financial impact of a ransomware attack through negotiation. Noescape, for example, tops the list with a significant 75% difference, meaning that on average, victims of this ransomware managed to negotiate a 75% reduction from the initial ransom demand. Revil comes in second with a 68% difference, indicating a substantial potential for negotiation with this group as well. Babuk and MountLocker also show considerable differences of 64% and 54% respectively, suggesting that negotiation can lead to significant reductions in ransom payments. Darkside, BlackBasta, Conti, Avos and Akira all have average differences ranging from 43% to 53%, further highlighting the potential for successful negotiation.

Avaddon and DragonForce have a 38% average difference, which, while lower than the previous groups, still represents a significant reduction in ransom payments. Hive, Lockbit3.0, BlackBasta and DarkSide have lower average raging from 21% and 18%, suggesting that they may be less inclined to negotiate on price. Overall, the data indicates that negotiation can be an effective strategy for reducing the financial impact of a ransomware attack, although the potential for success varies depending on the specific ransomware group involved. It is important to remember that these statistics represent averages, and the actual outcome of any negotiation will depend on a variety of factors, including the specific circumstances of the attack, the attacker’s motivation, and the victim’s negotiating skills.

NEGOTIATION PHASE

Along with the details of the requests and negotiations, I was able to access several copies of the chats that different criminal groups had with their victims, managing to extrapolate several components that were quite common among the different groups. Across these conversations, several common tactics emerge that demonstrate the attackers’ strategic approach to exerting pressure while also attempting to maintain an appearance of professionalism and credibility. These shared strategies reveal insights into how ransomware operators manipulate victims and steer negotiations.

One of the most prominent recurring themes in the dialogues is the careful balancing of threats and incentives. The attackers consistently utilize a combination of explicit threats and offers of cooperation to encourage swift payment. For instance, the threat of publicly disclosing the breach, often by announcing the compromised data on the attackers’ blog, is a frequent tactic. This is evident when the attacker states: “You have twenty-four hours to give us your decision regarding this deal or we will announce the breach on our blog.” This threat creates an additional layer of urgency beyond the mere restoration of the encrypted data, as it introduces reputational damage into the equation.

In each instance, the attackers escalate their threats by providing specific deadlines, emphasizing that if payment is not made within a short timeframe, they will leak the data: “If we don’t get your decision within next twenty-four hours we will be forced to announce your data leak on our blog.” This tactic is designed to corner the victim into action while framing the negotiation as time-sensitive. In parallel to these threats, the attackers attempt to build a sense of credibility by offering small concessions or proof of their capabilities. In practically all cases frequently provide a sample of decrypted files or offer to decrypt a few test files as a means of demonstrating that they possess the required decryption keys. This act serves to instill trust in the victim, showing that the attackers are capable of delivering on their promises once the ransom is paid. For example, they state: “Please review the decrypted files.”

Moreover in many cases it is the attacker him/herself who soffer to negotiate on the final ransom amount. Initial demands are often set very high, but often the attackers show flexibility, offering discounts for quick payments or agreeing to lower sums after assessing the financial capabilities of the victim. This is demonstrated when the attacker says: “In case you of quick payment, we will be able to consider a discount. We are going to work with 7 figures though.” This adaptability, although it appears as a gesture of goodwill, is a calculated move to ensure that some payment is made, rather than risk receiving nothing due to financial limitations on the victim’s part. Another shared tactic across the conversations is the attackers’ efforts to create an illusion of professionalism. They frame the negotiation as a business transaction, frequently assuring the victims that they are “honorable” in fulfilling their side of the deal. This is evident in a statement such as: “We value our reputation and honor all agreements we made.” They emphasize that, once payment is received, they will not return for further demands, will delete the stolen data, and will provide security reports detailing the vulnerabilities they exploited. However, in many instances, these promises are only partially fulfilled.

The security reports, when provided to victims, are often generic and lack specific details relevant to the victim’s infrastructure, suggesting that almost always the attackers aim to conclude the negotiation without delivering substantial or meaningful information to victims. For example, an example of “security report” is “None of your employees should open suspicious emails, suspicious links or download any files…“. Despite this, the appearance of professionalism serves to ease the victims’ concerns and make the negotiation seem more legitimate. In addition to these broad strategies, the attackers frequently reference the financial state of the victim organization as a negotiation tool. By claiming very often to have reviewed financial documents such as bank statements and audits, they tailor their ransom demands based on what they perceive the victim can afford. The attackers often say something like: “We’ve been looking through your bank statements, net income, cyber liability limits and financial audits. all information will help us to calculate our demand to you.” This tactic not only personalizes the threat but also increases the pressure on the victim, as it implies that the attackers have intimate knowledge of the company’s operations and financial standing. In some cases, the attackers directly suggest that the victim liquidate assets or explore other means of raising the ransom funds, further reinforcing the severity of the situation: “You can sell some of your assets or something but my bosses can’t go lower than $350,000.”

Throughout the conversations, the attackers maintain a firm but flexible approach. While they make it clear that they have the upper hand, they are willing to adjust their demands to ensure that the negotiation reaches a conclusion. This flexibility, however, is always balanced with reminders that the attackers are in control, and the victim must act quickly to avoid further consequences. The attackers’ ability to switch between offering concessions and issuing ultimatums creates a dynamic in which the victim is continuously pushed toward payment, while also being offered a way out through cooperation. For instance, they often state something like: “We appreciate your efforts to end this with us. The lowest number we can accept for the case is $250,000.”

Finally, ransomware negotiation tactics exhibits a calculated blend of threats, incentives, and displays of professionalism. The attackers exploit the victim’s fear of data exposure and operational disruption while offering just enough proof of their capability to restore the encrypted systems to keep the negotiations moving forward. By personalizing their demands, offering to lower ransom amounts in many cases and maintaining an appearance of legitimacy, the attackers create an environment where the victim feels pressured but also sees the payment of the ransom as the most viable solution. This blend of pressure and cooperation characterizes the core tactics employed across hundreds chat logs.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, ransomware negotiations are characterized by a combination of psychological pressure, manipulation of trust, and financial leverage. Attackers skillfully balance threats with reassurances, pushing victims toward payment while maintaining enough flexibility to close the deal. These tactics, honed over time, are increasingly effective, making ransomware one of the most persistent and damaging forms of cybercrime today. Finally, I would like to remember that paying ransoms is always to be discouraged for several strategic, legal, and security reasons. First and foremost, paying the ransom does not guarantee the recovery of encrypted data.

Even if the attackers provide a decryption key, it may be faulty or incomplete, leaving systems and data compromised despite the payment. Moreover, paying ransoms fuels criminal activities. When a ransomware gang successfully extorts payment, it encourages them to target more organizations or even reinfect the same victim, knowing that there is a chance of receiving payment again. From a legal and ethical perspective, paying ransoms could violate laws against organized crime, as many ransomware groups operate under the protection of international criminal organizations. In some jurisdictions, paying a ransom could even be illegal, especially if the funds are directed to groups that support illicit activities. Lastly, there is a significant reputational risk. Paying a ransom can damage the trust of customers as this could lead to long-term harm to the organization’s reputation, as well as potential financial losses from legal liabilities or lost business opportunities.